Ode to the Grange

How an uncommon community thrives in a small corner of Kilburn

We all have as much right to a local history as anyone, even if some of us arrived here only recently and from every corner of the globe.

Zadie Smith, from her story North-West London Blues

This is a small homage to my local park, the Kilburn Grange, and to its rich and unique life - a support network for a whole ecosystem and diverse community made of an infinite number of smaller communities who meet here at different times of the day, sometimes multiple times, for their ambling walks, meditations, constitutionals, relaxations, reflections, play or simply to breathe. The history outlined here is a result of scouring local history sources, embellished by my imagination. I have used many of my own photos, and I have also shamelessly borrowed from elsewhere, of course with permission and credit.

They say gratitude is an attitude, and it can only be a kind of grace that takes over the collection of urban foxes, squirrels, birds, trees, dogs and humans who meet every day at the Kilburn Grange Park between six and eight in the morning, as the dawn breaks and the sun begins her outward journey. Habibi and I make our way from our cosy apartment, our little oasis in this sprawling city, to this local open field, where even the trees seem to sway with a tenderness of care towards this strange collection of morning pilgrims.

M who by that time has already completed several rotations around the outside of the park perimeter as if she were casing the joint, waiting for us to open the gates, except she’s in her seventies with her handbag often tucked under her arm as if heading for the shops, and who kept us in anxiety for several weeks when she didn’t show up, and then collectively relieved when we found out she had gone to see family in Serbia. And on her return became overwhelmed to tears by the welcome she receives from strangers turned daily confidantes, as we all nod to her and she smiles and points, and pieces a few words together with effort in this new language she still hasn’t mastered. Soon after the bag was left at home, and she was seen to wave to each incomer with a familiarity and intimacy that makes her the new guardian of the morning crowd. Over time, and only to give us clarity on her unwavering discipline, did we piece together that she used to be the head nurse at a cardiac unit.

You hear B before you see him, as he hums the chorus to some lyrical masterpiece, and if the colour of the morning sky inspires he belts out in sonic prowess the reggae tunes of his youth, or those songs just breaking out into the charts, and you know he is kindness itself by the timbre of his voice and the confidences he shares, like how he adored his mother and how he learned to cook with her since the age of five and that’s the reason why he now makes food for children at schools, and runs private catering for every West Indian party or funeral in a three-mile radius. On some days he might be training a once rambunctious dog alongside his own well-behaved companion as he has that mystical way of taking the bite out of the dog, all the while doing push-ups and lifting himself up using the tree branches as anchors. On other days, the green is turned into a golf putting course where he practises his shots, while his dog runs and fetches the ever-improving efforts.

While at his heels is Y dressed always in one of her collection of hot pink jackets and striped exercise clothes moving to the rhythms of Tai Chi as she completes the inner circle of the park exactly five times, and then lurks behind the back trees to sing soprano to the birds, and then stops to do some breathing and movement exercises in the outdoor gym where she is soon surrounded by muscle men who are usually the last to turn up, and always surprised by the assembly of people and dogs shouting hellos and bursting with laughter, calling out the names of dogs like they were long-lost friends, and clearing any debris left from the feeding of night animals who ravage the full bins, all as the trees softly sway in the early morning breeze whispering many a thank-you.

I could keep populating this portrait of the Grange with endless sketches of characters so expressively unique, sometimes funny, at times tragic, always fully present and defiantly rich in spirit, and who gather in this small corner of North-West London each morning. Over the years, this place has become my second home; friendships have been built with ease and taken root in a communion found only among pilgrims.

For this morning ritual is no different from a daily pilgrimage from our private rooms to this open-air shrine, where we shrug off a restful or fitful night, for a date with the rising Sun, whether She’s in full attendance or playing hide and seek behind the clouds and rain, it matters not. We know She is there.

Some of you might argue why I gender the Sun feminine. It’s simply my intuition, as She arrives every morning to show us, her earthly friends, her unwavering and unconditional love. It would take only a quick deep-dive to remind us how language is not always neutral, it is also political. The Old English word for Sun was Sunne, a grammatically feminine word, until it slowly transmuted its gender in the late 16th century, heavy with its religious polemics and dogma most pronounced with the early Witch Trials, and where patriarchal structures were laid in concrete slabs over our Mother Earth in lands that crave the Sun the most.

The sweetness of that morning Sun on our faces when She arrives. Habibi and I linger strategically in that sweet spot located near the basketball courts, in the far-top corner of the green. Whether spring, summer, autumn or winter, this is the miracle spot where we receive the long rays of golden kisses that have travelled ninety-three million miles in such a hurry to reach our upturned faces, that they raced through the heavens in under nine minutes. There have been days when it’s taken me longer to remember where I was.

This daily gathering is its own form of worship, if worship were a faith or commitment to a communal place that holds you and offers you joy, insights, and friendships.

Wintering

This winter, the Christmas and New Year season feels very sentimental. Maybe it’s because this will be one of the last seasons I spend in this neighbourhood, a place to which I am bound by a deeply personal and complicated history.

This sentimentality is not trivial. I feel it as an early grieving response to the looming loss of a community that I have both cultivated and also been welcomed into.

The loose communities that we find in spiritual or religious gatherings were once entirely ordinary to us, but now it seems like it is more radical to join them, a brazen challenge to the strictures of the nuclear family, the tendency to stick within tight friendship groups, the shrinking away from the awe-inspiring. Congregations are elastic, stretching to take in all kinds of people, and bringing up unexpected perspectives and insights. We need them now more than ever.

Katherine May, from her book Wintering

This winter was also marked for me by reading the beautiful book by Katherine May on Wintering: The power of rest and retreat in difficult times.

Coming to the end of 2025, I felt a huge need to slow down and take care of myself, and I was not going to deny this need, Instead, I was going to carve the time out for relaxation. The year was unrelenting. The lessons fast and furious. Hard, tough, and so deep. I felt like I was back at university, but this time I was really doing the work, not just playing at being a student.

2025 was an opportunity for growth: to take charge of how we want to learn and grow, and not just be guided once again by the reactive infantilism of the mass media, or by sleep-walking technocrats, or by survival programming that keep us in endless Samsara, or by wounded figures in power and restless tech bros, lashing out where they might instead be learning how to lead with compassion.

Katherine’s book came to me as a balm for the spirit. She reminds us that we can’t just keep marching to the drums of a beat that does not oscillate, to the ticks of a clock that does not rest, as she puts it “one long haze of frantic activity, with all the meaning sheared away.”

That’s why we need to winter.

Winter does not only come as cold weather pulling us indoors and inwards, but can also appear as circumstances, events, setbacks, and opportunities. We need to retreat, in order that there is repair and care. In order that we can emerge again strong and ready for a new season of life.

The changes that take place in winter are a kind of alchemy, an enchantment performed by ordinary creatures…. Plants and animals don’t fight the winter; they don’t pretend it’s not happening and attempt to carry on living the same lives that they lived in the summer. They prepare. They adapt. They perform extraordinary acts of metamorphosis to get them through… Winter is not the death of the life cycle, but its crucible.

Katherine May

I’m not the same person I was even a year ago. This winter, here in my locale, I am seeing this community with fresh eyes, returning to it as one returns on pilgrimage, and in doing so making and remaking my story into one that feels better, more curious, more patient, and more alive.

Maybe to love a place is to start asking what it stood on before you arrived.

Romans and Engineers

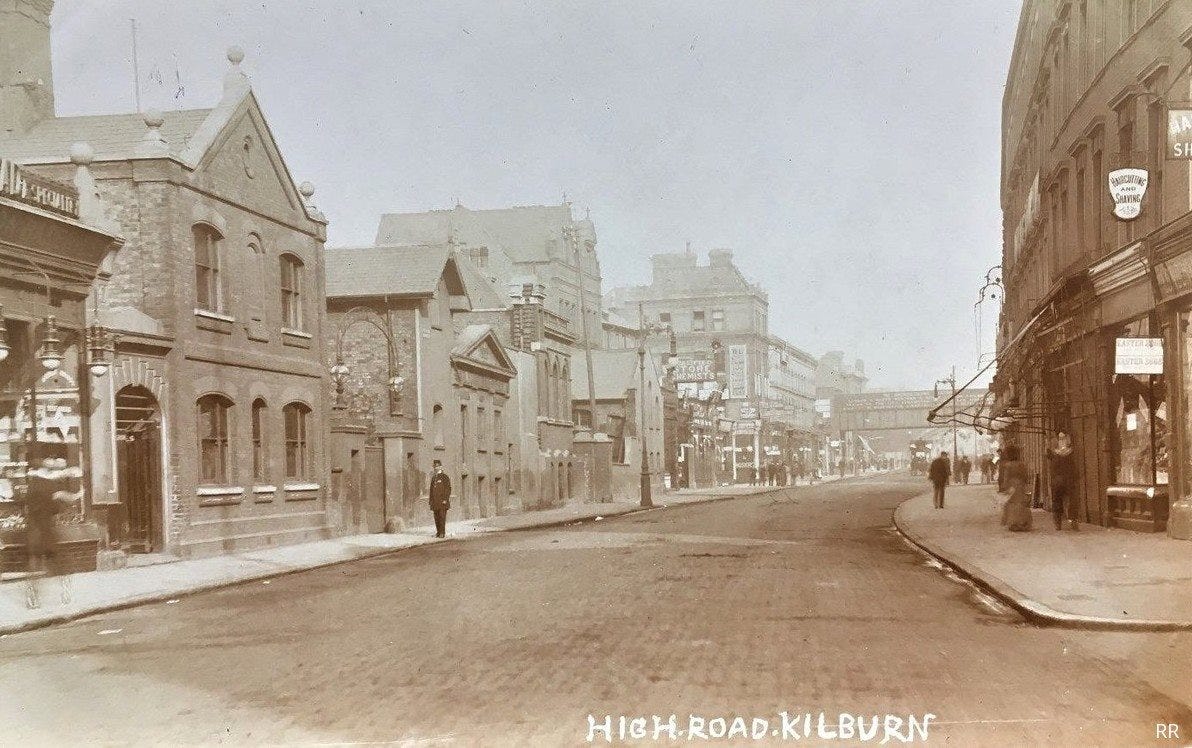

Kilburn Grange Park is a small city park nestled quietly behind the bustling Kilburn High Road to the east and the gentle rise through West Hampstead towards the higher perching reaches of Hampstead to the west. Today the High Road is a congested shopping stretch of the modern A5 Road, also known as Edgware Road and Maida Vale along its route.1

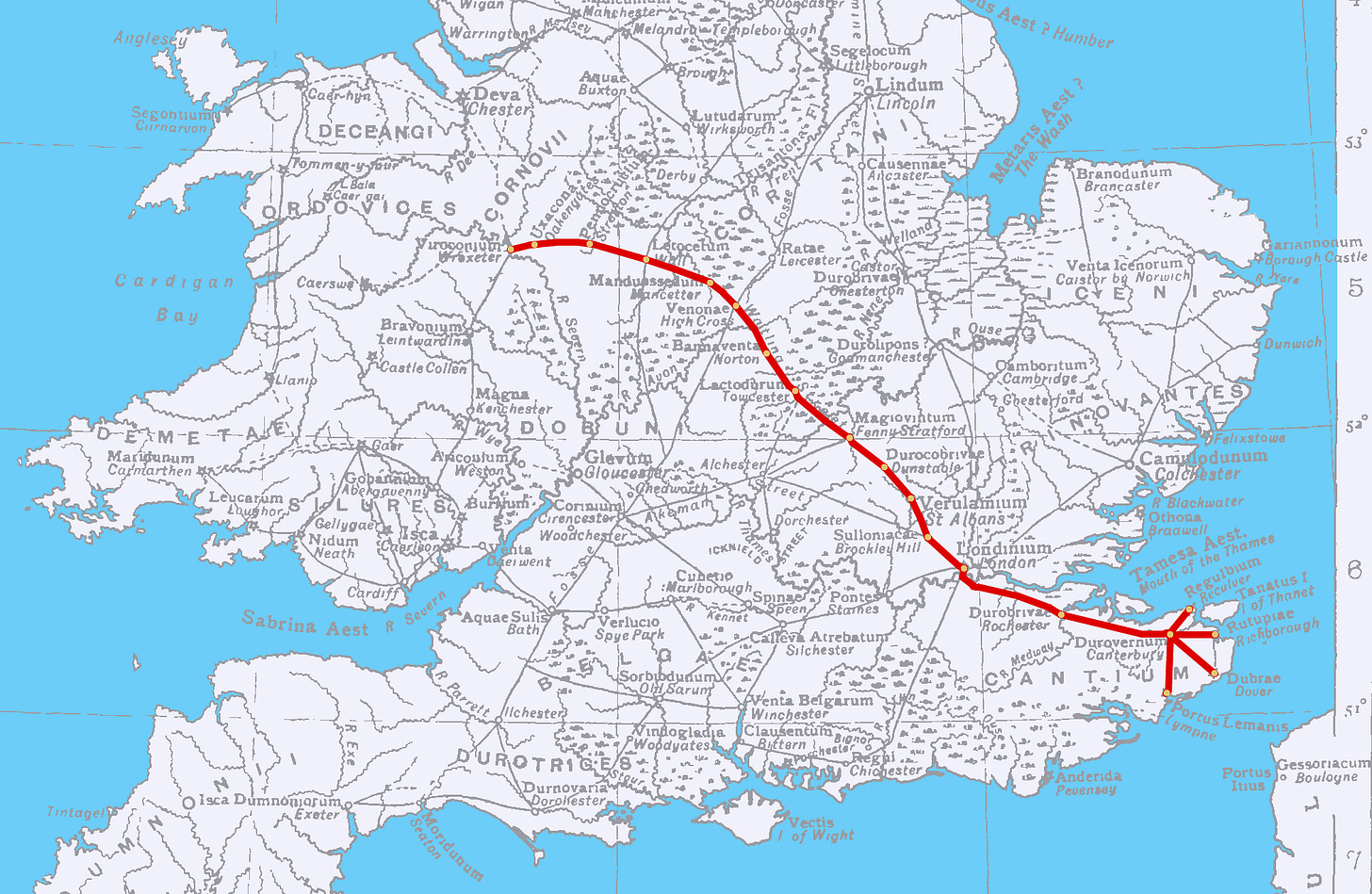

Those in the know would say with some authority that this major artery in our contemporary metropolis was once part of the Old Roman Road that ran from old Londinium to Wroxeter in Shropshire, near modern day Wales, the frontier post of the Roman army, and in its prime Britain’s fourth largest city. The road has since been extended all the way to the port of Holyhead in Wales, in a story that further embeds the humble Kilburn High Road in a far more illustrious history of the nation.

With the Act of Union 1800 unifying Great Britain and Ireland, it became necessary to improve communications between their capital cities. This led to an extraordinary act of Parliament resulting in the first ever major civilian state-funded road project since the Romans, which redesigned and rebuilt the existing Roman Road and extended it to the Irish Sea, under the guidance of Thomas Telford, the once humble Scottish stonemason, who became the country’s most famous engineer in a transformation worthy of the butterfly, and a lasting inspiration on how one man’s passion can lay the groundwork for opening up whole new worlds.

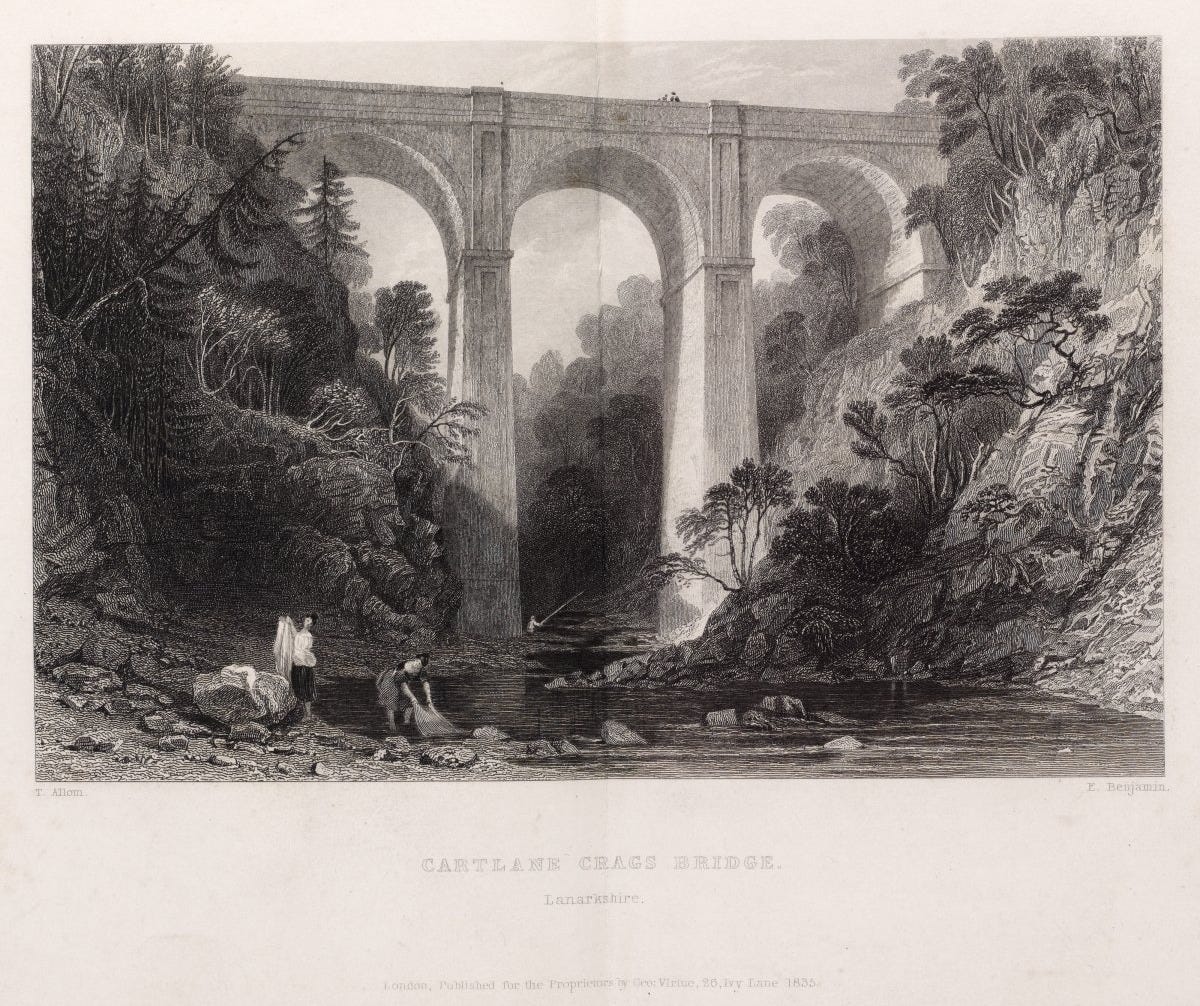

Telford, lovingly named the ‘Colossus of Roads’ was responsible for over nine hundred miles of roads, numerous bridges and some of the most iconic industrial canals and aqueducts in Great Britain such as the awe-inspiring Cartland Crags Bridge in Lancashire, the UNESCO heritage site Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, and the Menai Suspension Bridge, both in Wales, along with the impressive sixty-mile Caledonian Canal in Scotland connecting Loch Ness, Loch Lochy and Loch Oich.

Not one to be held back by land, Telford also turned his hand to improving harbours, docks, and piers, even designing the St Katharine Docks in London, which was later damaged by German bombardment in the last century destroying nearly all its original warehouses. Today, only some semblance of the original docks remains, most important is the interlinking of the East and West basins that still form the layout of the modern marina.

In a twist worthy of a magical kingdom, Telford the Engineer embodied the meaning of his name. The name Telford has roots in the Old French for taille fer meaning “he who cuts iron” or “iron-cleaver” or you can find it transformed in the Old English to mean “ford” which is the shallow part of a river or stream where a crossing can be made to the other side.

I wonder how many Telford roads and bridges I traversed with Habibi during our travels around the UK, and yet I only discovered him when I looked closer at home.

The Procession of Hermits, Pilgrims, Nuns and Knights

Back to the High Road, those same whispering people may also tell you that the Kilburn Priory was where the pilgrims stopped in Medieval times for rest and alms on their way to the shrines of Saint Alban, or closer by to Our Lady of Willesden who was also known as the Black Virgin of Willesden with her own surprising and unusual history which I may revisit in another letter.

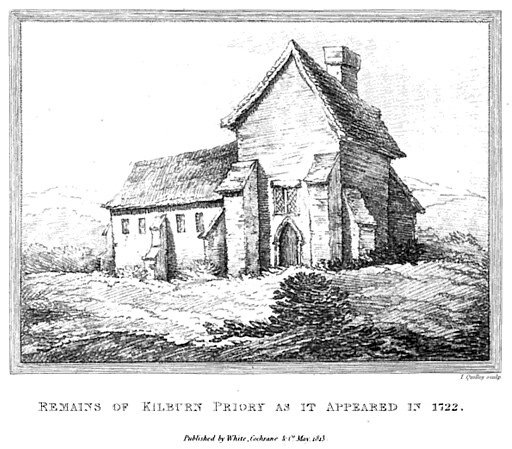

Located further down the High Road at what today is the intersection with Belsize Road, the Kilburn Priory of years past captures my imagination so much that I have made it the centre of a fictionalised story I am writing.

The recorded story goes that in the 12th century, in “Cuneburn,” there lived a hermit called Godwyn who built himself a small hermitage near a stream. He was so devout that he bequeathed the land and hermitage over to Westminster Abbey in 1134 which in turn handed it over to three formidable nuns, Emma, Gunhilda and Christina, to run it under the continued supervision of the godly Godwyn.

Emma, Gunhilda and Christina were former maids of honour to Queen Matilda, the consort of Henry I. They lived in a Kilburn Priory that can only be dreamed up now - one surrounded by mulberry trees, of which only one tree is said to have survived in a house in what is now St John’s Wood.

Soon after a church was erected on the site dedicated to St John the Baptist. And in exchange for prayers for their souls, the Abbot of Westminster gave the nuns an estate called Gara in the Manor of Knightsbridge at Kensington Gore, and the Priory continued to grow. Today you will know this as the premier part of the South Kensington area, on the south side of Hyde Park, connecting the Royal Albert Hall with the Royal College of Art, the Royal Geographical Society, and the Albert Memorial. To think that our modest Kilburn Priory and its procession of nuns for over four centuries had once controlled what has become some of London’s most illustrious real estate.

Back to the story.

Alongside the land, the Abbot also plied them with many gifts of wine and food. Yet even with all these benefits, the nuns continued to struggle and suffer continual debt due to the burdens of free hospitality they offered with their blessings, to both poor and rich traversing this busy pilgrimage road.

The procession of pilgrims was never ending, and the nuns could not refuse them. It was the duty of nuns to provide lodgings to pilgrims and travellers for as long as they needed. Some of these pilgrims would stay for days and weeks to form companies for protection before continuing the road to St Albans, where dense forests gave cover to thieves along the way.

Their efforts did not go unnoticed, and in appreciation more land and gifts were bequeathed to the nuns, including the manor of Wembley, estates in Hendon, Tottenham and Southwark, and the church at Cudham in Kent, all providing a mix of rental income and agricultural produce.

Still the Kilburn Priory never achieved wealth.

It did something much more astounding. It gave support and alms to pilgrims and travellers continuously for 402 years all the way up to the days of Anne Browne, the last prioress, who is believed to be a member of the noble house of Lord Montagu, when in 1536, Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries.

Henry VIII was famously fickle, someone I’ve always imagined as a sinister master reincarnator reappearing every so often in the form of a cruel and unreasonable leader surrounded by yes men, and who was unable to hold on to much for long, including his unfortunate wives. He quickly handed over the Kilburn Priory to the Order of the Knights of St John of Jerusalem, otherwise known as the Knights Hospitaller, in exchange for their more valuable manor in Paris Garden, Southwark. The Knights only lasted a few more years before their public dissolution in England, Wales and Ireland by that same fickle tyrant, and the land returned to the Crown once again before going into private hands.

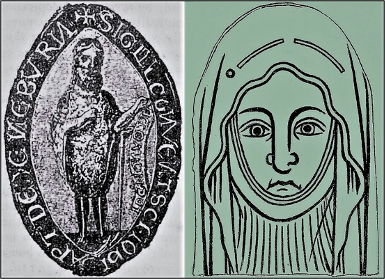

The only remaining relic of this remarkable local history which witnessed countless travellers, hermits, nuns, and knights, real estate booms and busts, and religious variety from its beginning as a Benedictine enclave to its transformation into Augustinian convent - is a small brass tablet held now in St Mary’s Church on the Priory Road believed to depict one of the prioresses, Emma de Sancto Omero.

Ancient Pathways

Traveller, your footprints

Are the path and nothing more;

Traveller, there is no path,

The path is made by walking.Antonio Machado, Traveller, There Is No Path

Conspiratorially, I can tell you that the history of the Kilburn High Road, this once holy pilgrimage pathway, is far older than the medieval hermits, nuns and knights.

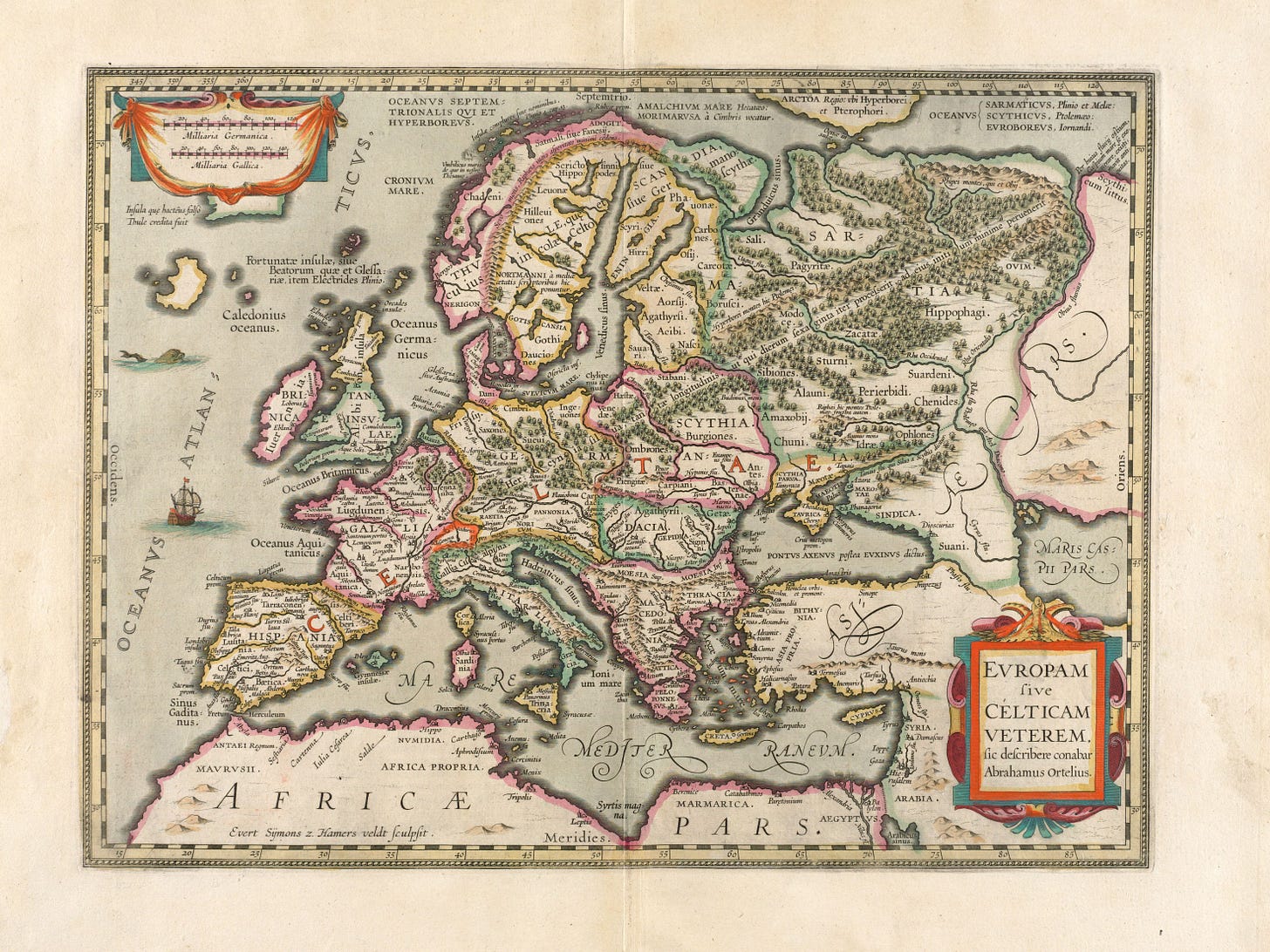

It is as old as the Celts and their Iron Age tribes who traversed it from Verlamion to Durovernum Cantiacorum, or what we know as modern-day St Albans and Canterbury, strongholds of the powerful Catuvellauni and Cantiaci tribes.

These early settlements were vital centres of economic activity, trade, craftsmanship and the diplomacy of ancient life; these would be transformed time and time again under new rulers, reigns, religions, rationales, reactions, responses, reflections and reverences.

The Catuvellauni and Cantiaci were the most prominent tribes of South-East Britain and dominated large territories. The Catuvellauni, a warrior aristocracy Belgic tribe whose name is thought to mean something similar to “battle-famous” or “warriors of the stronghold”, held the power North of the River Thames across what today would be Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire and parts of Cambridgeshire, Buckinghamshire, Essex and Northamptonshire, while the Cantiaci covered the areas South of the River Thames all the way to present-day Kent, and Eastern Surrey and Sussex.

It is evocative to think that the North/South divide in London which continues to exist today, and is part of my own City Imaginarium, has its roots as far back as the 1st century BC.

These were not just some simple tribes roaming the land.

They were hugely organised tribes that operated independently for hundred of years. Skilled and wealthy with a robust agricultural economy, they were producing their own currencies as early as 10 BC.

The Celts at times tend to be portrayed as these romantic figures strolling the gentle and endless primeval wilderness communing with nature. This was very much a product of an overactive imagination of 19th century romantic movements that were reacting to the industrialisation of their own societies.

The Celts, at least those surrounding London and the South-East, bear little resemblance to this wild romantic vision.

The perspectivation of history, shaped by the unmastered gaze of the present - is it like the colour and form decisions a weaver makes as they hum by the spinning wheel before they even set the loom? Perhaps you will end up with a tableau of pale wildflowers and gazelles, or one of brash reds and dark blues hanging in the halls of royalty. Do we dream the past as much as we dream our futures?

These Celts were the cosmopolitans of their day.

They were fine warriors, skilled metalworkers, craftsmen, artists, tradespeople and agricultural masters who lived in complex societies. They made intricate jewellery, finely crafted weaponry, and even embellished their pottery with motifs. They were hugely influenced by Continental Europe and negotiated sophisticated alliances to grow their wealth, dominion, trade routes, and bargaining power.

Their trade networks encompassed the Mediterranean cultures (Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans), Iberia, and Britain. Typical goods traded by the Celts included salt, slaves, iron, gold, and furs. These things were exchanged in a barter system for wine, amber, fine bronze, and pottery vessels, and scarce materials like ivory, coral, and coloured glass, which could be incorporated into Celtic manufactured goods. Trade also brought with it an exchange of ideas, particularly in the fields of technology, art, and religious practices. So, too, there was an increase in competition for resources that could be traded, which in turn brought an increase in tribal conflicts and fortified redoubts as well as war with, and ultimately conquest by, the Celts’ most powerful neighbours, the Romans.

Mark Cartwright from World History Encyclopedia

They were the builders of an infrastructure that still shapes and echoes today, and which we glimpse in the location of our modern shrines, the modern roads we travel on, and even the modern sentiments we have about our cities.

The most famous of the pre-Roman alliances between the tribes saw the Catuvellauni absorb the Cantiaci and another neighbouring tribe, the Trinovantes, who were located in the Northern Thames estuary area, otherwise known as modern-day Essex, Lower Suffolk, and parts of Greater London, into a much larger kingdom which made its capital at the Camulodunum, the main settlement of the Trinovantes. This later became the first capital of Roman Britain, and the city we know today as Colchester.

It is fascinating to think that these dynamic people, who were forging the world we would one day inherit, had already carved their major route of communication along what is now the Kilburn High Road so long ago.

We know very little of how these ancient tracks came to be.

Were they carved by instinct or topography, or were the infinite forces of wind and water working subtly over the ages with foresight to guide our future routes?

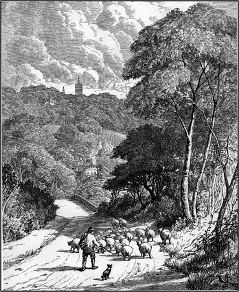

When the Romans arrived, they did not build Britain as many would like to believe, but engineered and expanded upon a web of ancient Celtic footpaths and trackways, a vibrant infrastructure of exchange and connection, which may have been superimposed on even earlier Neolithic and Bronze Age tracks, etched first by prehistoric footpaths and by herds of moving animals following winding natural routes that hugged the landscape in homage.

Beneath each road, there may lie an ancestry of movement, of extinct large mammals, of shifting weather formations, of bellowing winds, and tectonic sighs. The past becomes infinite the more we gain clarity on where we stand.

The most famous of these ancient lines is known as Watling Street, first traced by those early Britons, later adopted and paved by Romans to move their troops and supplies. It runs, in fragments and continuities, through the entire spine of our landscape.

Travelled on by Roman Emperors, it was traditionally cited as the field upon which Boudica, that formidable Iron Age Queen of the Iceni Tribe, was defeated by Suetonius Paulinus in AD 61, though the exact site has eluded our modern historical sleuths into either scholarly quarrel or maybe time’s own forgetting.

Watling Street was also mentioned in the Treaty of Wedmore in AD 878 between King Alfred and the Danes, who agreed to leave Wessex and settle on the Northern side of the street, while the Saxons stayed on the southern side.

The theme of the North and South is one that continues to dominate this small Isle and may find its fissures in old wounds and grievances, in family separations and centuries of obsessions.

Parts of Watling Street are still visible in the City of London, others now flow beneath the Edgware Road, Maida Vale, Telford’s bustling A5 artery, and that very pavement beneath our feet on the Kilburn High Road, which today still marks the boundary between the areas of Willesden and Hampstead.

For millennia these paths followed the contours of rivers, the curve of slope and valley. The Romans were the first to deviate from these natural lines. All this a far cry from our current highways and railway tracks designed for the modern obsessions of speed and efficiency, announcing direct routes that scar the land, zigzagging and criss-crossing to repurpose the quiet wisdom of those old paths.

Now, the soft and accommodating earth yields into submission under the mechanised conveyor belts for diapers, radios, patio furniture, flat-packed wardrobes, dog food, artificial ferns, trampolines, electric kettles, plastic toys shaped like fruit, inflatable mattresses, garden hoses, novelty Halloween costumes, discount blenders, scented bin liners, protein powder shakes, flat-screen televisions, frozen chickens, yoga mats, glass panels for skyscrapers, and whatever token capitalism insists must arrive before noon tomorrow.

Will our modern highways survive? Will they be softened and reclaimed by another imagination that follows? Or will our efforts at reductionism at any cost, to save a few pennies, and line a few wallets, simply evaporate over time, leaving barely a trace?

As for me, whenever I can, I take the longer route

It is always the most scenic. The most harmonic.

The most romantic.

An Elegant Order in Chaos

This modern-day Kilburn High Road whispers its past, and if you listen carefully, you can still hear the tired treads of pilgrims, the marching of Roman soldiers, and the farmers moving their goods beneath the drone of traffic, the rustle of shoppers, and the hustle of traders.

There is something here for everyone and maybe this has always been its destiny, renewed and remade contemporary with each generation.

The modern High Road may be traced back to that original hermit’s hamlet built on the banks of the river Cye Bourne, which in the 18th century became its own tourist destination drawing in the crowds for the medicinal powers of its springs.

As the pleasure seekers descended on the Kilburn Wells spa, the tea gardens blossomed into a cottage industry, forever memorialised by Dickens and Cruikshank and depicted so humorously in Sketches by Boz.

The heat is intense this afternoon….. What a dust and noise! Men and women — boys and girls — sweethearts and married people — babies in arms, and children in chaises — pipes and shrimps— cigars and periwinkles — tea and tobacco. Gentlemen, in alarmingwaistcoats, and steel watch-guards, promenading about, three abreast, with surprisingdignity …… — ladies, with great, long, white pocket-handkerchiefs like smalltable-cloths, in their hands, chasing one another on the grass in the most playful andinteresting manner, with the view of attracting the attention of the aforesaid gentlemen— husbands in perspective ordering bottles of ginger-beer for the objects of their affections, with a lavish disregard of expense; and the said objects washing down huge quantities of “shrimps” and “winkles,” with an equal disregard of their own bodily health and subsequent comfort — boys, with great silk hats just balanced on the top oftheir heads, smoking cigars, and trying to look as if they liked them — gentlemen in pink shirts and blue waistcoats, occasionally upsetting either themselves, or somebodyelse, with their own canes.

Some of the finery of these people provokes a smile, but they are all clean, and happy, and disposed to be good-natured and sociable.

Charles Dickens from “London Recreations”

The river has known many name variations over the years; as the Cuneburna, Keneburna, Keeleburne, Coldburne, Caleburn, Kilburn, Kilbrun Brook, The Bayswater, Bayswater River, Bayswater Rivulet, Serpentine River, The Bourne, Westburn Brook, the Ranelagh River and the Ranelagh Sewer, and today more commonly known as The Westbourne, which from her humble origins as a stream in Hampstead flowed down into the sacred River Thames, ruled by the mother goddess Isis and now by Old Father Thames, and many other gods and goddesses in the forgotten vaults of memory.

The river Cye Bourne, this ancient and revered river, once ran freely above ground - emerging at the highpoint of Hampstead, pushed out of the ground by the promise of a view, gaining strength and momentum, as she made her way down sliding through the West End, which was original name of the village of West Hampstead before it was borrowed for entertainment, through Kilburn, then Bayswater, Knightsbridge, until she joined the Thames at Chelsea - before she was later diverted underwater to form the Serpentine Lake for the fancy of Queen Caroline and her many dogs.

It is this river that still rises in winter, soaking the green of Kilburn Grange Park to the seasonal despair of the dog owners who return home with ruined shoes, and muddy companions in need of more than one shower.

This past year for my birthday in December, Habibi and I spent 8 hours walking from West Hampstead down to Chelsea Harbour then following the Thames Path with the ambition to get to Greenwich but found ourselves faltering at St Paul’s, at the mercy of the biting weather and the river air, as we crossed and criss-crossed bridges to grab a view from each side of the divide. As I commit these words to the page, I’m amused to realise that, without planning or knowing, we had been following the path of the Westbourne all along.

Does life imitate or direct, or do our natural ramblings somehow follow the ancient tracks?

Or do the ancient river paths still call to us from under the ground, energetically orchestrating our routes?

Although my flat is officially located on the old winding rural track of West End Lane in West Hampstead which runs parallel to the High Road, and which some more fancy neighbours prefer to call The South Hampstead Conservation Area, it is in closer proximity to the Kilburn High Road than to the elegant and boutique cafes at the top of West End Lane in the Village, and in its depth of feeling and its constant rhythmic fluctuation from chaos to order and back, much more alive.

My sister and I have for long now fondly called the High Road, the ‘Road of a Thousand Fools’ for the sheer spectacle of humanity and diverse expressions of life that hits you the moment you step onto it. This nickname was inspired by the local epithet given to the stretch of road to Port Sudan in North Africa where order and chaos danced together in a joyful and tense embrace, long before this horrific war in Sudan disparaged visitations.

On any given day there would be a theatre of activity from trucks groaning with goods, glossy cars filled with families headed to the coast, donkey drawn carts full of daily necessities or bursting with bags of wheat, trailers pulling luxury boats for men who grew too powerful too quickly, and where a Beja, from the Cushites, a pastoral people who nomadically roam those areas, and which Rudyard Kipling famously named in a colonial epithet “the Fuzzy Wuzzies” on account of their unique huge crown of fuzzy hair first recorded in early Egyptian rock paintings from 2000 BC, may at any moment decide to stop, without warning, as if by random, in the middle of the road to make their version of coffee, a ceremony that can take anywhere from thirty minutes to a few hours, and through which the stream of traffic would slow down, weave and form a slow-moving halo around him. Not even modernity dared disturb this ritual.

The only time I saw this, we were driving east from the capital Khartoum, another underserved capital with a remarkable history - itself a tripartite city where the Nile either joins together or separates into the Blue and White Nile depending on the romance story you prefer – on our way to visit with my cousins by the Red Sea and go out on the boats.

As the full heat of the East African sun hammered the roof of our small car with my body feeling the ache of the bumpy road, I was set for monotony, for a long boring dusty ride. Instead, quickly dispossessed of that notion, I stared in awe at the miracle of the Beja’s magnetism and majestic presence, in his humble status and worn-out clothing, to commandeer the reverence of every vehicle on the road simply by deciding to make a cup of coffee.

Kilburn, the most interesting street in Europe

Zadie Smith is not wrong.

I am the luckiest novelist in the world to live so close to the most interesting street in Europe.

Zadie Smith from The Joy of Kilburn

Here, the rituals are urban, unfolding in dozens of small improvised dramas: debates and reconciliations, street vendors setting up their kingdoms of commerce, families going out for a special meal to celebrate, friends idling together over coffee, the old men in the cash only cafes on the side streets, musicians dragging amplifiers like they were priceless relics, schoolchildren moving in glossy shoals, shopkeepers sweeping yesterday’s stories from their thresholds.

Although there are many more people with a million different missions, if you look more closely you can begin to see them as modern pilgrims arriving from all corners of this great city, from across the country, across the seas, to buy, to sell, coming to be seen, to exist in this experiment. It is a literal crossroads where cultures meet without dissolving, and yet there is a familiarity, many kindnesses, a real community in this urban jungle.

It also couldn’t exist anywhere else in the world.

The particular history and story of this Island, the might and breadth of the British Empire that swallowed so many lands under its flag, now finds itself roosting and melting together in a special multicultural expression with a unique flavour that can only be found in this slice of the Great Metropolitan of London. A slice flavoured with the spices from the Middle East, the Irish pubs and working men clubs, the generational Caribbean homes, and the multitudes of South Indian restaurants that have been here for decades.

I always joke that whatever you’re looking for, or not looking for, you can find on the Kilburn High Road: Algerian Butchers, One Dollar Stores, Mobile Phone Outlets, Discount Shoe Shops, Quality Shoe Shops, Sport Stores, Charity shops, High Street Fashion, Boutiques, Perfumeries, Notaries, Accountants, Solicitors, Gyms, The Library, Music Shops, Chinese Medicine Doctors, Key Cutting, Sewing, Laundromats, Branded Coffee Shops, Turkish Stores, Kebab Shops, Upscale Sushi, Romanian Bakers, Glass Makers, Framers, Opticians, Medical Centres, Hotels, Trendy Cafes, Tattoo Artists, Nail Technicians, Hairdressers, Barbers, Irish Pubs, Italian Gourmet Pizza, Regular Italian Delis, Greek Tavernas, Afghani Restaurants, Chinese Takeaways, Gelato Counters, Speciality Cake, Mediterranean, African and Asian food shops, West African Tailors, Ethiopian speciality shops, and the list goes on. I don’t think I’ve even scratched the surface.

As Peter Ackroyd writes in London Under:

Tread carefully over the pavements of London, for you are treading on skin — a skein of stone that covers rivers, tunnels, springs and passages, crypts and sewers, creeping things that will never see the light of day.

And nowhere is that truer than here.

The History of The Grange Estate

I found more than one unlikely friend when Habibi, my mighty dog companion, came into my life, and I was led to navigate the back roads of my neighbourhood emerging into the Kilburn Grange Park.

A few minutes from my home, this space became part of my daily map, where Habibi has her first morning run, where I became part of a community of dog owners, with the self-appointed name of the Kilburn Pawesomes, shepherded by dog-whisperers who taught me as much about community as they did about how to train my dog recall.

This eight-and-a-half-acre open space is a surviving offshoot of the old Grange Estate which was bequeathed into public ownership opening its doors to residents on the 1st of May 1913. But there was an earlier story here too.

Nearly four hundred years after the nuns had come and gone, the knights were dispersed, and the crown had cashed out, there was a private world here.

What became the park was then part of the grounds of an estate with an 1830s mansion called The Grange, which stood back from Kilburn High Road with carriage gates and gardens.

For most of the 19th century the Peters family lived here, holding on even as terraced streets rose tightly around them, pressing in from every side like eager onlookers.

Thomas Peters, a wealthy coach-builder for Queen Victoria, moved into the mansion in 1834 just a few years after it was built. On his death, the estate passed down to his son John Winpenny Peters who married Ada Britannia Beckers in 1863.

Ada was young, beautiful and social, although she soon met with the tragedy of losing her only daughter Pauline to scarlet fever, and shortly after with the death of her husband. As a widow, she was constrained by the terms of her husband’s will which stipulated that she could enjoy the estate as a living tenant as long as she did not remarry, otherwise the estate would revert to the Peters family.

This did not stop her. She threw herself into the world of parties and literary salons, where she entertained her guests with her harp playing, alongside her soon-acquired, and long-time lover, The Marquis de Leuville, a man worthy of his own story due to the rampant rumours that he was a Victorian fraud.

Favoured by splendid weather, Mrs Peters had a delightful garden party on Saturday afternoon. Nearly 300 invitations had been sent out. There was the best opportunity for enjoyment by all, whether in the exercise of the lawn tennis ground, or in promenading within sight of Dan Godfrey and his band of Grenadier Guards, or in roaming about the ample and beautiful grounds, or in quietly sitting within the shelter of the numerous umbrella tents that skirted the lawn. Many of the company took the opportunity of viewing the choice collection of works of art and mementoes of visits to Italy and other parts of the Continent. In the evening, a concert was given under the able direction of Mr Sidney Smith, (another Kilburn resident).

The Kilburn Times, August 1885

By the time Ada Peters died in 1910, the surrounding neighbourhood had long since become a dense patchwork of workers’ houses, schools, and factory yards. Open space was vanishing. The locals wanted the land for breathing. Developers wanted it for building. The Peters heirs wanted it for profit.

The mansion’s contents, its oil paintings, carriages, statues, were auctioned off. The building was sold and pulled down.

Oswald Stoll, a showman of considerable ambition, bought the estate intending to build a grand theatre to rival his London Coliseum in St Martin’s Lane, near Leicester Square. Progress overtook him, and instead the 2,312 seat Grange Cinema opened on 30 July 1914 which remained the largest in Kilburn for a couple of decades before the Gaumont State overtook it to be the largest cinema in Europe with 4,000 seats.

The cinema was designed by one Edward A Stone, who brought to life the Astoria Finsbury Park, and the Prince Edward Theatre on Old Compton Street. The fact that such highly regarded designers and entertainers invested their energy in the Kilburn High Road during the golden age of cinema, celebrates its importance at the time as a vital artery of the city.

The Grange Cinema finally closed on 14 July 1975 and later that year became a nightclub called Butty’s, catering to the Irish community. It was named after Michael ‘Butty’ Sugrue from Kerry, who was widely known as ‘Ireland’s Strongest Man’.

Butty was a man seemingly unstoppable. Not only a wrestler and circus performer, he was also an entrepreneur, a master publicist, and a publican who ran the Admiral Nelson in Carlton Vale, Kilburn, and the Wellington in Shepherd’s Bush. It was said, and widely believed, that he could lift four fifty-six-pound weights fixed to a cart axle. As if that were not enough, and almost beyond belief, he was also said to drag a cart filled with ten men using only a rope clenched between his teeth.

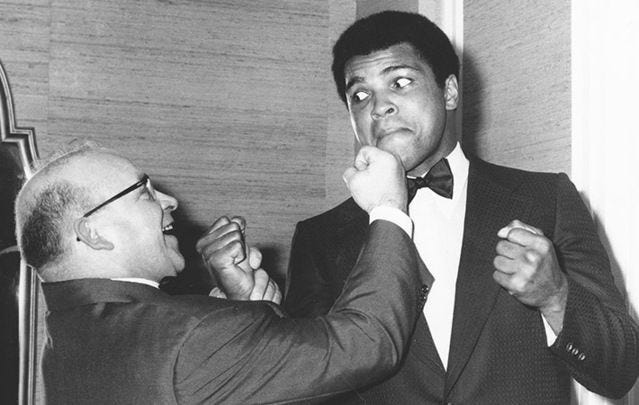

It was Butty who persuaded Muhammad Ali to travel to Dublin in July 1972 to fight his sparring partner, Alvin ‘Blue’ Lewis. He was also credited with persuading one of his barmen, Mick Meaney, to attempt the world record for being buried alive, rounding up journalists and huge crowds to witness Mick emerge sixty-one days later.

After Butty’s club had its run, it was converted and became the Kilburn National Ballroom or the Kilburn National Club or the Irish National Club depending on who you talk to, where Johnny Cash and David Bowie performed beneath glittering lights and leaking ceilings.

After decades of concerts, film shoots (including scenes for Backbeat about the Beatles), wrestling exhibitions, and community dances, the building transformed again after attempts to demolish and rebuild in the 1990s failed as it had by now received Grade II historic listing status.

Its latest transmutation follows the theme of so many of these grand ballrooms across London, now being converted into churches, first the Victory Christian Centre, and currently The Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, with their own individual histories not devoid of theatre, and have faced serious controversy and allegations over the years from money-laundering to operating as a cult to name a few, but this is a subject best suited for others to explore.

Its façade still carries the bones of its many past lives.

The Gardens

It’s hard to imagine Kilburn without the green lung of Grange Park today.

Dick Weindling and Marianne Colloms, Local Historians authors of Kilburn and West Hampstead Past

The open gardens and land itself were nearly lost to speculation when the estate was sold. But a coalition of local councils, campaigners, and ordinary residents fought to reclaim it as common ground. They scraped together contributions from Hampstead, Middlesex, Willesden, and everyday donors, placing coins in local collection tins. Eventually, the London County Council struck a deal with Stoll for the eight and a half acres of open land to be preserved as public land in exchange for £19,500, the equivalent of £2.9 million today.

The gardens remained.

A bandstand was built.

A model-boat pond.

Footpaths that curved with the curves of the land.

On 1 May 1913, quietly and without ceremony, Kilburn Grange Park opened. No speech, no ribbon.

Just gates unlocked.

People entered, children played, friends idled together, and Irish youth were striking shinty balls across the grass.

And from that day forward, the land belonged to us.

I can only imagine the lives of the saints that have gone through this small patch of green and used it daily for their solace in moments of need. Size matters only in relation to depth, and in that this small park is unlimited.

The park blossomed into something even deeper during the period of the Covid Lockdown of 2020, where the blocks to physical companionship unlocked stranger circles of communion amongst neighbours who have not spoken to each other for years, but who would now pass each other as we re-discovered the roads, buildings and open spaces of our locale.

This celebration of where we live formed a new kind of familiarity that was not there before between software engineers, garbage collectors, old ladies with fascinating histories often overlooked, horticulturists, nurses, lawyers, economists, psychologists, students, marketing assistants, bakers, graphic designers, publicans, café owners, artists, actors, musicians, teachers, data scientists, doctors, publicists, editors, retirees, diplomats, civil servants, personal trainers, accountants, investment bankers, the employed and the unemployed, so many children, and many, many dogs. All part of an improvised village held together by shared mornings and afternoons under an open sky.

The first western gardens were those in the Mediterranean basin. There in the desert areas stretching from North Africa to the valleys of the Euphrates, the so-called cradle of civilization, where plants were first grown for crops by settled communities, garden enclosures were also constructed. Gardens emphasized the contrast between two separate worlds: the outer one where nature remained awe-inspiringly in control and an inner artificially created sanctuary, a refuge for man and plants from the burning desert, where shade trees and cool canals refreshed the spirit and ensured growth.

Penelope Hobhouse

And now, like every city park, it stands as both refuge and palimpsest - a former estate turned communal sanctuary, a reminder that sometimes the most radical act in a metropolis is simply to leave a piece of ground unbuilt.

Contemporary Park Life

Kilburn Grange Park is small compared to other local London parks, barely three and a half hectares, but it holds multitudes.

We have two children play areas, a tennis court, a basketball court, a rose garden, a dog run, an outdoor gym with custom made bolted down equipment that can probably survive a nuclear war, a triangular community garden that awakens interest then slumbers by mysterious schedules, a café seldom open, a workshop dreaming itself into existence, and at its centre a great open green used for lounging, picnics, barbecues, dog meets, child ball games, yoga, boxercise, children parties, birthday parties, Eid celebrations, Jehovah’s Witnesses presentations, music circles, festivals, volleyball on the last Sunday of every month, meets, and any general idleness or activity you can imagine.

I think of Kilburn Grange Park as a litmus test.

There is no other place in London that is the sight of such controversy or a refuge of spontaneity, depending on what side of the divide you sit on.

Some arrive and see chaos.

Others arrive and see a citadel of freedom.

I measure my affinity with a person by their reaction to the Grange - a place I consider to the most democratic public urban space - imperfect, unruly, alive.

The Grange operates its own internal logic allowing it to accommodate everyone from tired first-time parents who try to loll their babies to sleep by circling the green surprised that it even exists, gym fanatics and champion boxing stars who train their local students here, groups of children and parents who stream through before and after school in varying states of hurriedness, contemplative wanderers who find a shade area to write or read, lovers who intertwine under a tree, giggling teenagers who are deep in confidential speak in the rose gardens, or causing havoc racing up and down in their scooters only to be told off or slow down, the young from the music colleges across the way who come to sing and strum their guitars, the heavy drinkers deep in enthusiastic philosophical conversation or depressive silences, the homeless who find solace when greeted warmly like lost friends, young hipsters, the well healed residents of West Hampstead, artists from the Kingsgate Studios, and the many others of us who have made this an extension of our home.

It invites the open, the quirky, the weary, the hopeful, the fun loving, the teary, the tired, the lonely, and the downtrodden. We all co-exist here and share the same patch of ground.

Arrive early if you wish, as we now have community opening powers after a campaign I helped run, and you will be met with the early birds, the young and the elderly; the migrants and refugees who can’t sleep anymore chased by darker reminisces driven to this green oasis to savour the friendliness of the dog owners who all greet each other with the warmth of best friends; the daily commuters who crisscross through it to get to any of the six stations and multiple bus stops that surround it; and of course the long-time locals on either side who revolve around the green keeping the park clean by picking up the rubbish spread out by the night creatures, the wandering foxes and gourmand squirrels and crows that have a penchant for pizza, KFC and Doner kebabs especially the ones from the Turkish takeaway just across the road.

Just this week I saw something incredible.

L who is a recent addition to our morning pilgrims has been coming to lay healthy seeds and feed for the pigeons, who through sloppy urban living have grown accustomed to McDonalds and other fast foods left out by well-meaning people. He works for a bird charity, and told me that their reputation is underserved, that they’ve been loyal to us since we learned to draw, our earliest of cave drawings depicting them, and that they spend years in mourning after they lose their mates. This particular morning, we ran into each other at the park entrance, Habibi running ahead, and as we got close to the rose garden, near where he lays their food, there was suddenly a roar of pigeons overhead, easily a hundred of them, suddenly fluttering their wings and swooping down and up surrounding us, like an audience clapping and whooping for the favourite singer as they enter the stage. They recognise L and they recognise health.

I don’t mean to paint a picture of Paradise.

It is definitely not that. For who wants to live in an idealised Paradise of someone else’s imagination.

The park needs more investment and attention, and I hope it receives the care it deserves, for what it offers is so much more than can be quantified by an Excel sheet or master plans for a future that is not yet arriving.

We need more care to be shown to this vital resource, one of the most subscribed parks in the city, used by so many. Yet the treads of careless vehicles mark our green, the garbage is not picked up regularly, and the trees and bushes are left to their own accord, as if this park matters less than those up the road in wealthier Primrose Hill and Hampstead.

We have a wealth of trees here: oak, yew, ash, silver birch, hornbeam, London plane, and even the not-so-common coast redwoods. There are also exotic species: tree-of-heaven, hybrid black poplar, common lime, and sycamore. They need expert attention and thoughtful care.

You cannot change any society unless you take responsibility for it, unless you see yourself as belonging to it and responsible for changing it.

Grace Lee Boggs

Here, in this layered, lively corner of North-West London, there is something better happening: a living co-creation taking place, shaped by the converging landscapes of people and their histories, of arrivals and departures, of times lived and grieved; the living layers of the city meeting, like the old rivers still running beneath.

My research on Kilburn started nearly a year or so ago for a time travelling whodunnit YA novel. However, a few months ago I was drawn to urgently write this homage to the Grange.

It must be the sentimental mood I’m in. Most of the information for this piece comes from widely available archival material and blogs on the internet.

You can also check out these local books: Kilburn and West Hampstead Past, Dick Weindling & Marianne Colloms, Historical Publications, 1999; Streets and Characters of Kilburn and South Hampstead, Marianne Colloms &Dick Weindling, Camden History Society; The Joy of Kilburn, Introduction by Zadie Smith, Photographs by John Morrison, Culbrepar Publishing

Internet Sources include: Brent Council: Uncovering Kilburns History series; British Pilgrimage Trust; Camden Guides; Camden Local Studies and Archives; History of Kilburn and West Hampstead; A History of St Mary’s Church and School; Kilburn and St John’s Wood, Institute of Historical Research: British History Online; Kilburn Museum Labs; Institute of Civil Engineers: Thomas Telford; Irish Post: The Day Muhammed Ali Came to Ireland; Journal of Archaelogical Studies: The afterlife of Roman roads in England; Library of Congress: Gender Shifts in the History of English; The London Museum: the Sacred River Thames; London’s Lost Rivers: The Westboourne; Native Tribes of Britain; Select Surnames; Thames21; Trade in Ancient Celtic Europe; Underground Map: The Kilburn Priory NW6; UK Parliament: An Act for the Union of Great Britain and Ireland; Wembley Matters; West Hampstead Life; Wilsden Local History: Kilburn; World History Encyclopedia

‘Does life imitate or direct, or do our natural ramblings somehow follow the ancient tracks?’

‘Or do the ancient river paths still call to us from under the ground, energetically orchestrating our routes?’

So much here that resonates Muna!

Sometimes we just need to stop, feel and let it all unravel, just like nature does at this time of the year.

When the land is dormant, the trees naked, the birds silent, deep underneath the soil decays, matures, and gets ready for the inevitable new growth.

As smart-minded seekers we can get seduced by light, illumination, the sun … but - yes! - let’s also remember to honour darkness for the stillness, maturation and inner strength it brings to our lives.

Community. Without this, life is hard, life is lonely, life is unfulfilling. Connect. Put your phone down. Get to know people in person. Be vulnerable. Be kind.

Be a ‘villager’, be of service to your community, the ground at your feet. Plant seeds that offer new life.

Most of us would benefit from focusing on strengthening our weight-bearing net of supportive relationships, and our local community is a good place to start (and from experience made easier by having a dog).

I recently became a director of the residents board of the building I live in, and set up a gardening committee to encourage people to get to know each other through a shared involvement with the communal grounds.

It's a time and energy commitment when I am not exactly light on responsibilities already, but it felt like the right thing to do, and so far so good (and challenging!).